TG Lingappa composed some of Kannada’s masterpieces. His sense of music was impeccable and he infused it with a rich theatricality

When you listen to the music of TG Lingappa, you hear the rich textures of the leg harmonium. The grand instrument gets its evocativeness from a combination of pumping that is deep and shallow, quick and slow — weaving a luxuriant tapestry of sounds. The crescendos and diminuendos that a leg harmonium achieves gives it a high mimetic character, in fact, the company dramas of yesteryear gave this instrument centre stage.

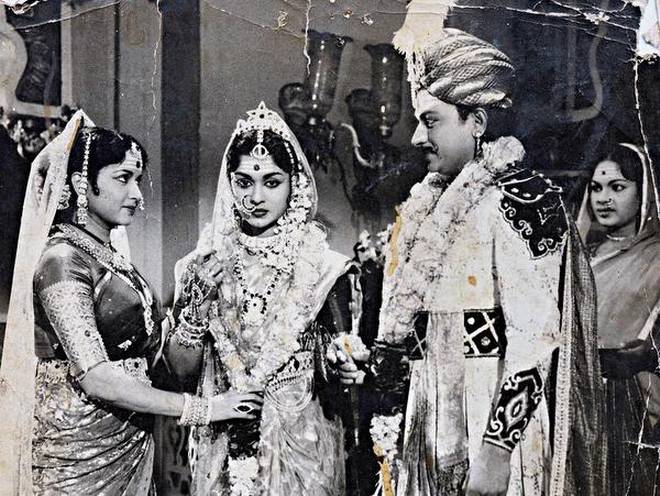

His father’s music certainly made a huge impact on TG Lingappa. Govindarajulu Naidu, Lingappa’s father, played the leg harmonium in company dramas. Story goes that the actor-singer MK Thyagaraja Bhagavathar was Naidu’s good friend and often visited their residence and had several singing sessions. KB Sundarambal, who was also a theatre artiste and later made it big in Tamil cinema, was Naidu’s disciple. Lingappa’s father sold musical instruments and the astute young boy could play almost every instrument that he set his eyes on. When the family moved from Tiruchi to Madras, the young Lingappa looked for opportunities in cinema. Theatre did become a thing of the past, a world that they had left behind, but it remained the eternal conscience of his musical expression.

Music in a theatre production has a specific purpose: at the cost of under-theorising it, one could say it heightens the mood. But more than seeing music as redolent or suggestive, it is important to understand what a piece of music does. If cinema can be seen as an extension of theatre, for Lingappa music was a piece of theatre too. So, he not merely made music for cinema, but also created a complementary cinematic narrative through music. An extremely gifted musician, Lingappa could play several instruments and made a living from orchestra in his early days. This perhaps gave him a clear picture of the music that each of these instruments could generate and as one sees in his film music orchestration, Lingappa does a phenomenal job of layering of sound.

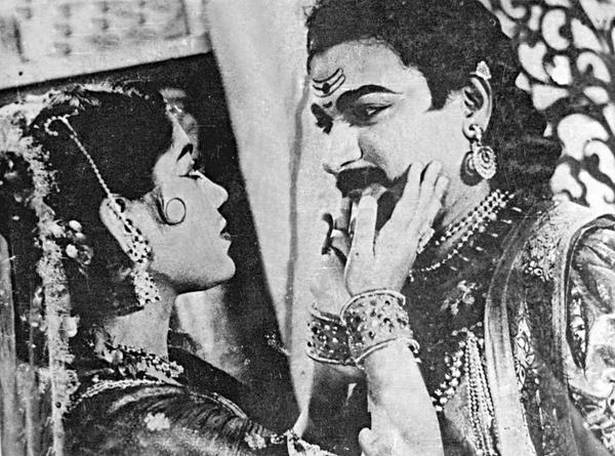

This can be illustrated through some of his works. Let’s take “Yaaru Tiliyaru Ninna Bhujabalada Parakrama” from the film Babruvahana (1977). The song is a dialogue, a verbal contest to begin with. Lingappa sets it to the highly dramatic, traditional kanda padya rendering style, but with the sharp, instrumental interludes he prepares you for the conquest that is to come after this exchange of words. To emphasize on his theatre influence, throughout this song (for that matter any song of Lingappa), not once are the words overshadowed by music: in fact, you can see how there are points where the song lets go of the tune and articulates it in the spoken word style as emphatically as music. This song is a wonderful coming together of two artistes from theatre background – Lingappa and Rajkumar. It requires enormous courage for a playback singer to sing just to the drone of the tanpura, and Rajkumar produces a masterpiece. Of course, PB Sreenivos who is Rajkumar’s co-singer, isn’t far behind. There is yet another short piece in the film, “Barasidilu badidante” which is also rendered in a similar style. The song opens with stunning violin passages that are akin to those in a symphonic orchestra. In both these songs, you can see Lingappa’s signature style, that is to change the raga or melodic harmony to heighten the drama. In “Aradhisuve Madanari” from the same film, all musical tools like raga portrayal, swara prasthara, konnakol, and tani avarthanam, become dramatic techniques.

Let’s consider three songs that would perhaps be broadly classified as devotional: “Shiva Shiva Endare” (Bhaktha Siriyala, 1980), “Jaya Jaya Samba Sadashiva Shankara” (Guru Shishyaru, 1981) and “Yaarige Yaaruntu” (Gaali Gopura, 1962). He interprets all the three differently – the first two are eulogies with upbeat tunes and an elaborate orchestra. In fact, in “Jaya Jaya” he uses instruments like chande and cymbals to give Lord Shiva his many dimensions. The third is a Purandara Dasa composition and Lingappa gives it a mellow narration without violating the philosophical core. It is clear that Lingappa was not thinking merely about the melodic composition: words, intent and the context formed the marrow of his work.

Lingappa was a versatile composer. He composed songs of different kinds, making it hard to believe that he composed them all. He made extensive use of sitar, veena and violins. Listen to “Ninna Neenu Maretarenu” (Devara Kannu, 1975) – he blends both schemes of Indian music, despite the violin passages which have a western orientation. “Entha Sogasu” (Taayige Takka Maga) is a stylish composition with an RD Burman kind of orchestration. The slow and soothing lullaby “Pavadisu Paalaksha” (Sati Shakti, 1963) in Malkauns is surely the best. “Jaari biddiye O Jaana” in Kedar is a brilliant composition: it works completely on syncopation like the verses in a qawwali. Janaki’s rendition is liltingly memorable. Of course, “Maatege migilada devarilla” is everyone’s hummable favourite.

Lingappa’s time also had other brilliant composers like MV Raju, GK Venkatesh, Vijay Bhaskar and others. But each of these musicians brought an amazing variety and authenticity to film music. Though all of them came from different backgrounds, they not only knew Indian music, but had studied Western music as well. But they way their music embodied all these different musical idioms is a fascinating study in itself. To understand TG Lingappa through the dramatic element is therefore, just one of the ways of looking at this superb musician. There can be several other perspectives. Lingappa’s music, like that of the leg harmonium, fills the ears, and the heart too. This is but a cursory look.

Inner Voice is a fortnightly column on film music.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Entertainment> Inner Voice – Movies / by Deepa Ganesh / May 22nd, 2018