Bengaluru :

Plaques detail the contributions of the three Tagores — Abanindranath, Gaganendranath, Rabindranath — and various art movements in the country at National Gallery of Modern Art on Palace Road. But no boards speak of the significance of the heritage structure that houses the collections of rare paintings — Manikyavelu Mansion.

A document in NGMA’s official files, titled Excerpts from Karnataka Government Gazetteer and signed by its former owner Vilum Manickavelu Mudaliar’s granddaughter Vitto Bai, tells you that this once belonged to the Yuvaraja of Mysore.

Mudaliar, it reads, was the third son of a poor family. He married into an aristocratic family and became a successful ‘business magnate’ after taking manganese and chrome mines on lease. He acquired this building, the document says, ‘during his early years’, and called it Manickavelu House. While reliable history books say it was sold to him, the record of the sale perhaps remains unknown, says historian and researcher Arun Prasad.

Officials in the NGMA say Mudaliar and his family lived in the mansion for some years. “But due to a domestic problem, they defaulted payments either to a bank or the government, and the house was put on auction,” says an official. It was acquired by the City Improvement Trust Board, the erstwhile BDA, and then transferred to the Housing Board in the 1960s. The Ministry of Kannada and Culture, which has taken it on lease, sub-leased it to the Ministry of Culture in 2000, when it became the chosen location for NGMA’s southern centre.

As for when the mansion was built, again records are elusive. “It’s neighboured by several century-old colonial bungalows, including the Balabrooie Guest House,” says Prasad. Hence, it’s probably safe to assume ManiIf you wander in its 3.5-acre campus, and look beyond the official records, you might catch snatches of a fascinating oral history account: Mudaliar, on a visit to Bengaluru, stumbled upon the colonial-style house when it belonged to the Yuvaraja of Mysore. Impressed, he sought entry and was refused until he greased some palms. After a tour around the mansion, he vowed he would one day come to own it.kyavelu Mansion dates back to that time, he adds.

If you wander in its 3.5-acre campus, and look beyond the official records, you might catch snatches of a fascinating oral history account: Mudaliar, on a visit to Bengaluru, stumbled upon the colonial-style house when it belonged to the Yuvaraja of Mysore. Impressed, he sought entry and was refused until he greased some palms. After a tour around the mansion, he vowed he would one day come to own it.

Indra Rajaa, daughter of Mudaliar’s granddaughter Vitto Bai, says her generation, brought up in Madhya Pradesh, is rather removed from their Bengaluru connection. “My maternal mother, Manickavelu’s only daughter, moved to Kotagiri after marriage,” she says. “She died a month after giving birth to my mother, who was brought up by her paternal uncle and his wife. My mother thought they were her parents till she got married.”

In 2003, the year she passed away, 67-year-old Vitto Bai visited the mansion with her husband. “She said she got a royal reception by the officials there, and was very happy,” her daughter says. Rajaa tried locating the house when she was last in the city. “I asked for Manickavelu’s mansion, but no one seemed to know where it was,” she says.

The Chennai-based chartered accountant recalls that an ‘uncle’, one of her clients who had met Mudaliar, had told her that great grandfather was a ‘generous man’. She quotes him: “He would willingly feed any number of people, but would refuse loans.”

But Mudaliar’s descendants are scattered across the city, says architect Naresh Narasimhan of Venkatramanan Associates, involved with the restoration and design of the new wings. “It is said he lived atop a hill in Rajajinagar, next to the one Iscon is on. He owned a lot of land in Mahalaxmi Layout, named after his daughter,” he says.

He says although the house is prominently British colonial in architecture, it features some Indian decorative elements on the outside.

When Narasimhan began visiting the site, what he calls the biggest bungalow in Bengaluru had a kitchen in the back. “It was in ruins, so we took it out and built the new galleries there,” he says.

In 2003, when restoration and construction began, the heritage building needed plugging of leaks, to say the least. “Water used to seep in,” says Rehana Shah, currently Bengaluru NGMA’s curator, who was posted here from the headquarters in Delhi to oversee the work. “The entire building was built with brick, with mud plastering,” says Narasimhan, adding that most structures back then were not constructed to last.

The auditorium too, built – according to Narasimhan – when the property was with a UN body before it was acquired by the government, also required work. “We replaced the roof,” Shah says. “And extended the stage, originally designed for talks,” he adds. The first couple of rows of seats were taken off to make room for this, and the hall now accommodates 168 people.

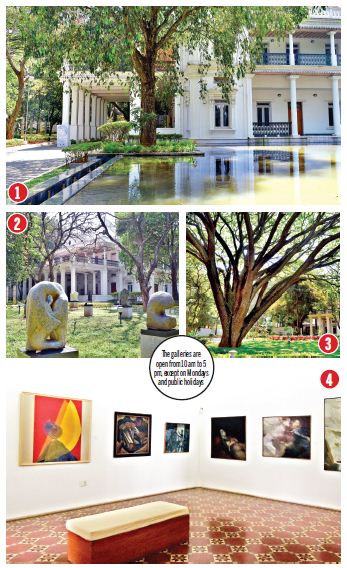

So the heritage building is like a central diamond, with the new additions – two galleries a museum shop and the cafeteria – like the ring around it, Narasimhan says. “That’s why there’s a pool next to the old mansion. Together with its reflection, the mansion forms a spectacular image in the evenings. The pool’s pump keeps its water moving, cleaning out fallen leaves.”

Tree Treasure

During the restoration and construction, the team of architects and Central Public Works Department officials took care to retain all the tress. “Next to the cafeteria stands the biggest, and probably the oldest rubber tree I’ve seen,” says Narasimhan.

The trees probably have their own stories to tell, says Prasad, for many of them have been around since the bungalow was built. Tree walks are conducted here regularly, and a part of the city’s tree festival, Neralu, was also held here.

“The trees here are truly grand,” says Janani Eswar, who conducted one of the festival’s sessions. “They have been allowed to grow undisturbed as they would be in a rain forest. Finding a spot like this in the city is very rare.” Visitors must not miss the nearly 150-ft tall banayan the back corner and a huge raintree in front, she says.

The Gallery and Museum

“As early as 1989, the state government proposed that the bungalow should be converted into a museum,” says historian Arun Prasad. “And the Centre agreed.”

In 2000, the Ministry of Culture took over the building for the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) and the foundation stone for the new structure was laid in 2001, during S M Krishna’s government. Work began in 2003 and continued right up to 2008. A 1, 260 sq metre gallery block, where exhibitions are organised, was added to the 1,551 sq metre art museum in the heritage building on the walls of which hang works of unknown artists alongside greats like Raja Ravi Varma, Jaimini Roy and Amrita Sher Gil. “This is perhaps the only colonial structure, located in such an aesthetic setting, that has been aptly converted into a museum – a museum with a collection no other in South India has,” says Prasad. “The extension has been made without damaging the original structure. Even the wooden panel flooring and the ornamental windows have been retained.”

source: http://www.newindianexpress.com / The New Indian Express / Home> Cities> Bengaluru / by Chetana Divya Vasudev / February 25th, 2016

1 thought on “Mansion’s Forgotten its Manikyavelu”