“‘Suragi’… this flower from the Malnad region, which takes me back to my childhood, grows more fragrant as it wilts. At a time when my health is failing, I wish to be like the suragi,” wrote URA in his preface to his autobiography in Kannada, published in 2012. S.R. Ramakrishna, who has distilled the essence of this suragi and made its delicate fragrance waft further beyond Kannada country, has ensured it an ‘afterlife’ through his sensitive translation of the text.

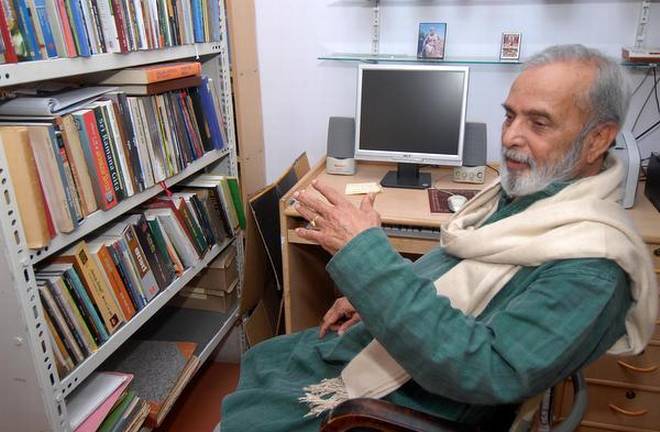

After Tagore, if there was one cultural icon at the national level with a similar kind of reach, it was URA. A master storyteller, URA authored many a modern classic such as Samskara, Bharathipura, and Avasthe, several short story collections, along with a prolific body of writing covering literary criticism and essays on culture and politics. While he had written and spoken about his life, his inspirations, and his politics all along at different venues, his autobiography brings together the varied skeins of his complex and colourful life, complementing his literary landscape.

If URA was an engaging presence, it was because he was truly engaged with everything — little and big — that was happening around him. And his autobiography bears testimony to this unique feature of his personality.

Spread over 10 chapters, the work covers crucial aspects of his life: childhood, student days, domestic life, teaching career, writing and creativity, and his experience as Vice-chancellor of Mahatma Gandhi University, Chairman of National Book Trust and Sahitya Akademi. Not to speak of the controversies that marked his journey as a ‘critical insider’ who kept a strict vigil on his social and cultural world and his side of the story.

While the contents page bravely attempts to arrange his life into these categories, the complexity of his lived experience and the even more complex understanding he has of that life do not allow for a linear, straightforward narrative. And all for the better. What we have is a richly textured narrative which combines experience and reflection, the lyrical and the discursive. The style was the man.

URA’s autobiography bears an organic relation to the intellectual and writer he was. A large part of his writing was already autobiographical, especially his stories and novels, which have drawn heavily from his childhood in Malnad region and his later years in Mysuru.

As Ja. Naa. Tejashree — his collaborator who collated and organised the material — notes, while his experience shapes a particular structure of thought in his creative works, the socio-political world that shaped his experience is foregrounded in the autobiography. Thus the text is best read as a political and cultural biography of his times — its hopes and fears, utopias and dystopias.

Ramakrishna, well-known for his creative translations, has provided a fitting ‘saath’ to URA and his collaborator. Based on his intimate knowledge of URA’s milieu, he plays around with English, using his discretion to leave certain words untranslated.

He has followed the shifting contours of the narrative, comfortably moving from the lyrical to the discursive. However, some rigorous copy-editing, especially of the starting chapters, would have made for better readability.

It is surprising that the translation does not carry the name of the collaborator on the cover page, a feature that marks the original text. The original carries a foreword by URA and another by Tejashree which describe the intent and processes involved in the making of this text, which is crucial to reading it as a mediated text.

Charismatic persona

Also, the Kannada original carries at the end a detailed list of URA’s writings, speeches, papers and presentations, as well as awards and honours, along with dates. Including these features of the original would have made the text an even more useful resource for URA scholars.

Despite the candid effort at capturing his life, one wonders if URA remains outside of his text. Could it be that the narrative is so largely social and outward that his inward, creative self has been subdued?

Or is it that URA’s towering achievements and his charismatic persona are hard to contain in words — like the quote from Eliot that URA uses, “Trying to use words… each venture… is a raid on the inarticulate”?

The man had donned so many hats and combined so many spaces and times in one lifetime that his irrepressible spirit cannot be contained within the material body of words. Perhaps this is why Girish Kasaravalli’s film on him was also titled Ananthamurthy: Not a Biography, but a Hypothesis.

To say that a large part of URA still lies outside of his autobiography is to pay homage to the élan vital of the man who engaged with his cultural and political world with exemplary commitment till his last day. Suragi is successful in gesturing towards this phenomenon called URA.

The writer is a teacher and a translator who works with Kannada and English.

Suragi; U.R. Ananthamurthy, trs S.R. Ramakrishna, Oxford University Press,₹650

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Translation / by Venamala Vishwanatha / March 17th, 2018